The Mississippi Blues Project is up and running! The “big bang” on Sunday afternoon August 20th featured the Cedric Burnside Project and Big George Brock in a stunning, earth-shaking concert in a large tent stage at the Philadelphia Folk Festival.

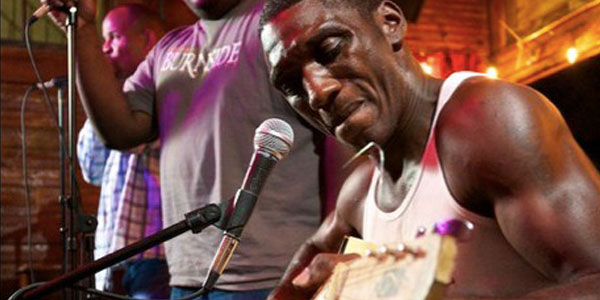

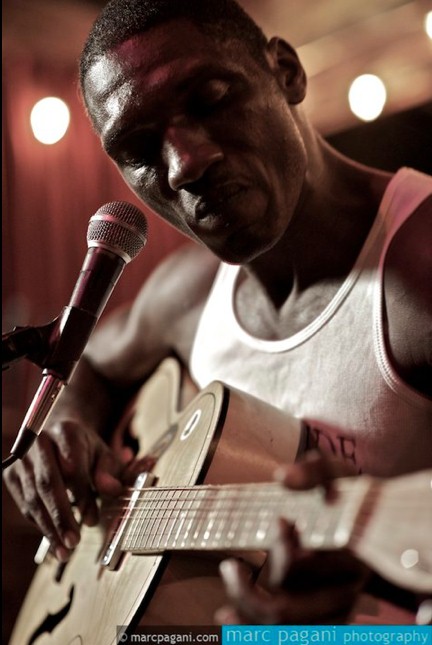

The Cedric Burnside Project, a two-man outfit featuring Cedric Burnside on drums and Trenton Ayers on guitar, put down what might be called a “gold-medal” performance of modern Mississippi blues. Burnside’s awe-inspiring skills on the drums, and the artistry and athleticism of his playing no doubt left vivid memories in the minds of the many people crowding up to the stage, dancing, hollering, clapping hands, and perhaps wondering, as I was at times, how this was humanly possible. At times his sticks hit the cymbals in such a rapid-fire fashion that, from where I sat, some sort of optical illusion was occurring and it looked like the sticks were “eating” the cymbals as they flashed downward.

Cedric Burnside is the grandson of the unforgettable R. L. Burnside. Their relationship was very close, and Cedric often echoes his grandfather’s sound and style, especially when he says “Well, well, well” between songs – – which at this point is a Burnside signature element, with the vowel in “well” halfway between “well” and “whale.” The music is rooted in tradition but also fully contemporary both in topics and style, incorporating elements of hip-hop.

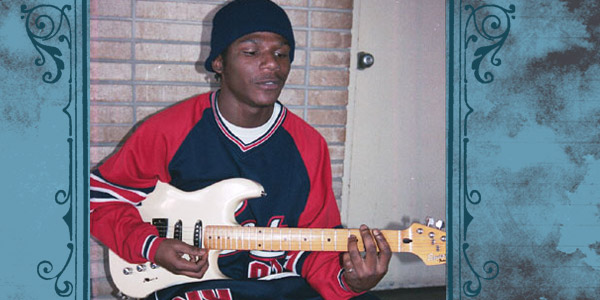

Guitarist Trenton Ayers was a dazzler, and I wish I’d had a chance to talk to him about his style. At one point between songs he strummed his guitar, and it sounded out-of-tune to me. He didn’t tune much, though, and when he went into the next song he got exactly the notes he wanted. Using a slide and bending strings, I suspect that Ayers in some ways plays the guitar the way a violinist or cellist plays. They don’t have frets on their instruments, and they know how to find the exact note they want without them.

A second guitar sat in a stand for the entire set. This was Cedric’s guitar. He plays in a simple but distinctive hill country style, and the only thing I could say that was missing in this inspiring show was that he did not walk over to his guitar and play a song or two on it. I suspect that he felt that the energy rising from his drums in the music they were playing was too compelling to modulate on-the-fly that afternoon. Of course that means we’ve got to get him back here again sometime!

Following the Cedric Burnside Project’s set would be a daunting challenge for any performer of any kind of music, but 80-year-old Big George Brock seemed up to the task. Brock is almost blind at this point, and has some hearing loss and problems with his hands, but none of that prevented him from singing the blues the way only an authentic blues singer can, and playing his harmonica with aplomb.

Brock was regally attired in robes, with a cape and crown, and his band was top-notch. He also brought with him singer Clarine Wagner, making her first appearance in this part of the country (Brock appeared some years ago at the Pocono Blues Festival). She warmed up the tent with “So Many Times” and the popular standard “Let The Good Times Roll.” Her appearance on Brock’s latest album “I Got To Keep My Bedroom Door Locked” is also her recording debut. Brock’s wonderful sense of humor comes through on the title track of this album, which he performed in the middle of his set.

In their own differing and very individual ways both Brock and Burnside made treasured memories in the opening event of The Mississippi Blues Project. What happens after the “big bang?” Well we don’t know it all, but everything expands and stars are formed. There’s a lot more still to happen in the coming year. Well, well, well…

{ 0 comments }